Delaying the Inevitable

A Fabian Strategy on Inflation

In the second Punic War, the Roman general Quintus Fabius deemed it imprudent to fight Hannibal in a direct battle, owing to the latter’s tactical brilliance. Instead, he employed a strategy of delay whereby he would avoid direct encounters with the Phoenician forces and seek victory by extending Hannibal’s lines of supply to the point of breaking, and thus earning the cognomen Cunctator1.

Though criticized by his political competitors and demeaned by the Plebs, his strategy proved effective and later led to Hannibal’s defeat by Scipio Africanus. The strategy is markedly effective when defending but cannot provide the basis for a successful attack. Sometimes it pays to delay, but sometimes the fight must be brought to the enemy, as was demonstrated by the success of Scipio in defeating the great scourge of Rome on his home soil in Africa.

As the Federal Reserve pivots from holding off inflation to addressing incipient labor market weakness, it should examine which strategy it ought now to employ.

Consumer Prices Are Moderating

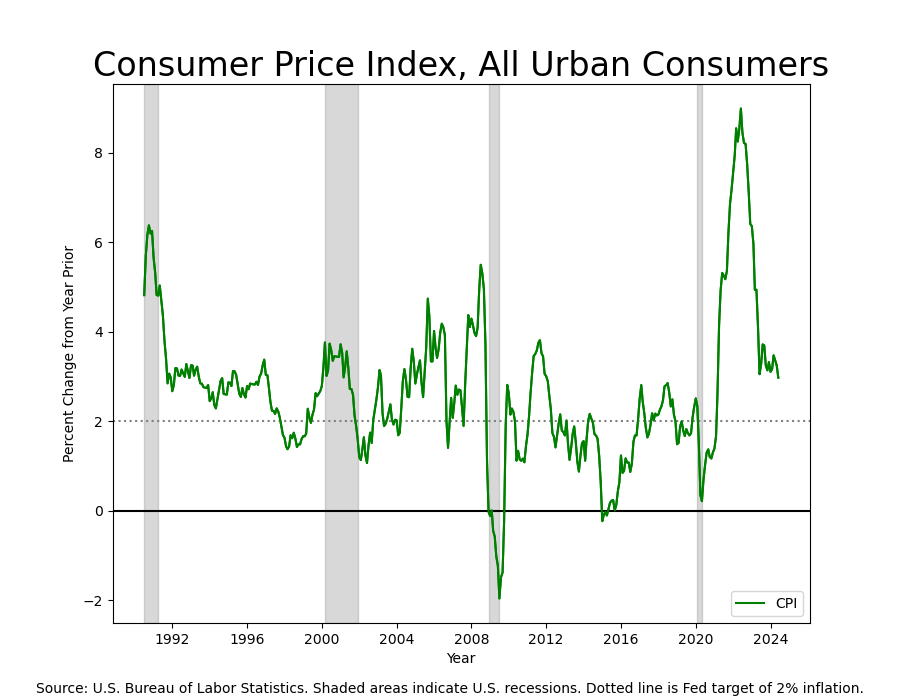

The inflation rate as measured by the not-fatally-flawed Consumer Price Index (CPI) fell again in June, registering 3.0% Year-over-Year (YoY) compared with 3.3% YoY the month prior. The rate has fallen for the third month in a row, confirming a downward trend.

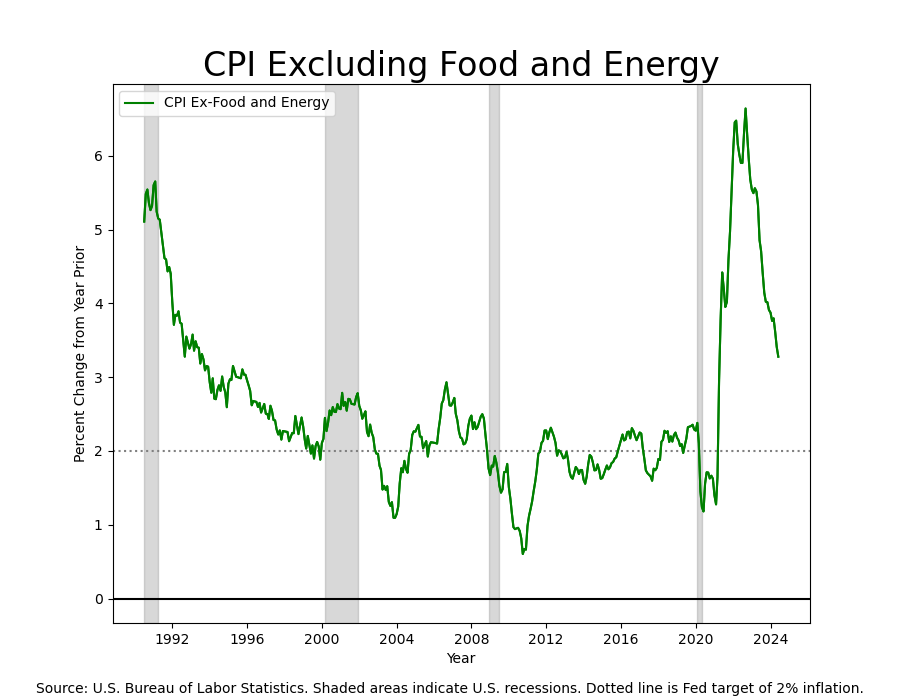

Excluding the volatile elements food and energy, the core inflation rate also fell from 3.4% YoY to 3.3% YoY.

Disinflation continues, notching the mildest reading since June of 2023. The Federal Reserve’s campaign to lower interest rates received an important fillip from the slower pace of energy price increases, with gasoline and fuel oil decreases offsetting higher gas prices. Prices for transportation and shelter also rose more slowly, contributing to the reprieve. The Futures market wasted little time in adjusting bets as to the timing and number of interest rate cuts it expects in 2024.

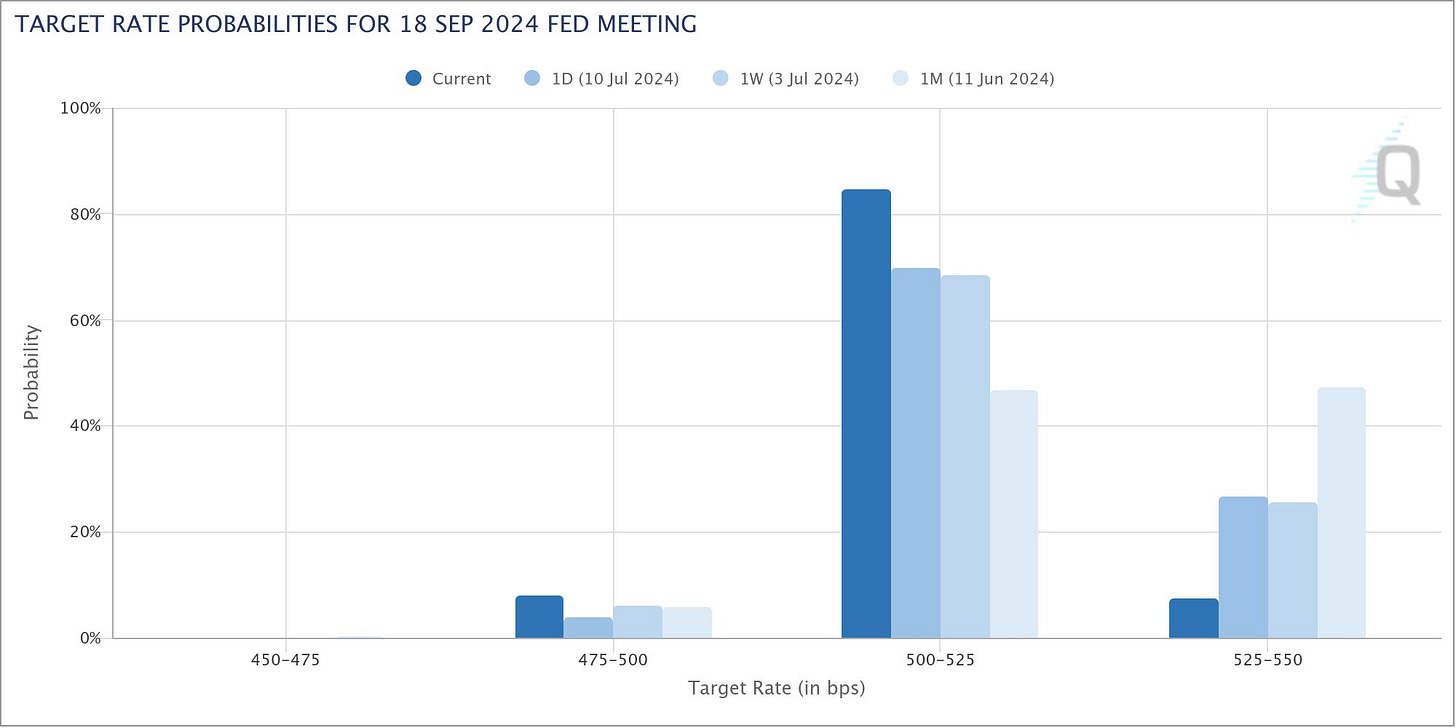

Futures pricing suggests a better than 90% chance of an interest rate cut by or at the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee meeting in September. Those odds increase to 97% by November, at which time there’s also estimated to be a 50/50 chance of two rate cuts. Odds are 50/50 that there will be a third rate cut by December.

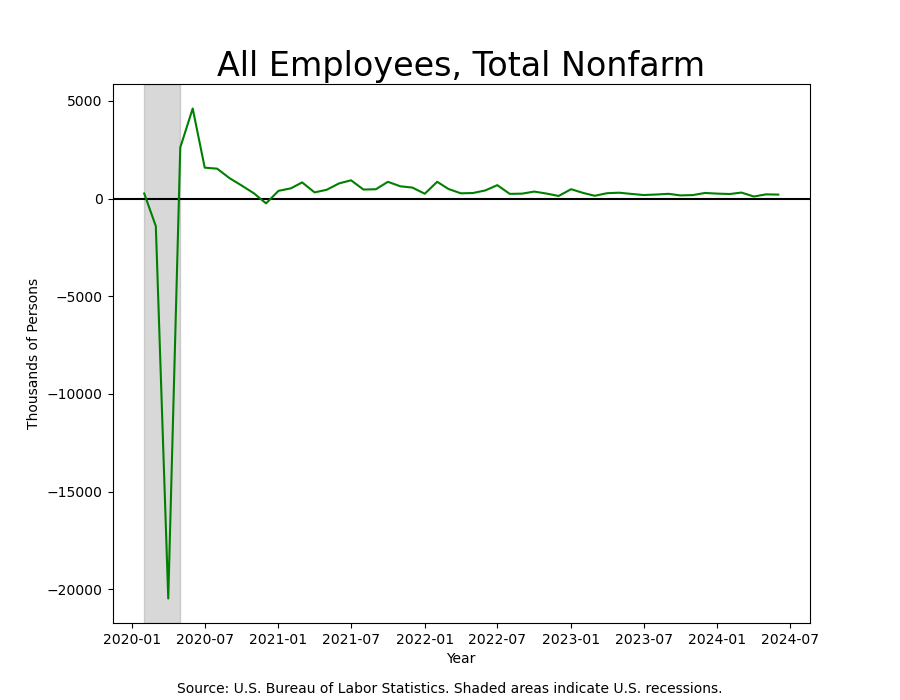

The Labor Market Is the Story, Not Inflation

While the declining rate of price increases provides evidence of a slowing economy, to our mind the labor market is where the real (in)action is. The growth in non-farm payrolls continues apace but was revised lower for the prior month and lost a step. Payroll growth remains consistent with economic expansion, but the strength of payroll growth is sapping to a small degree.

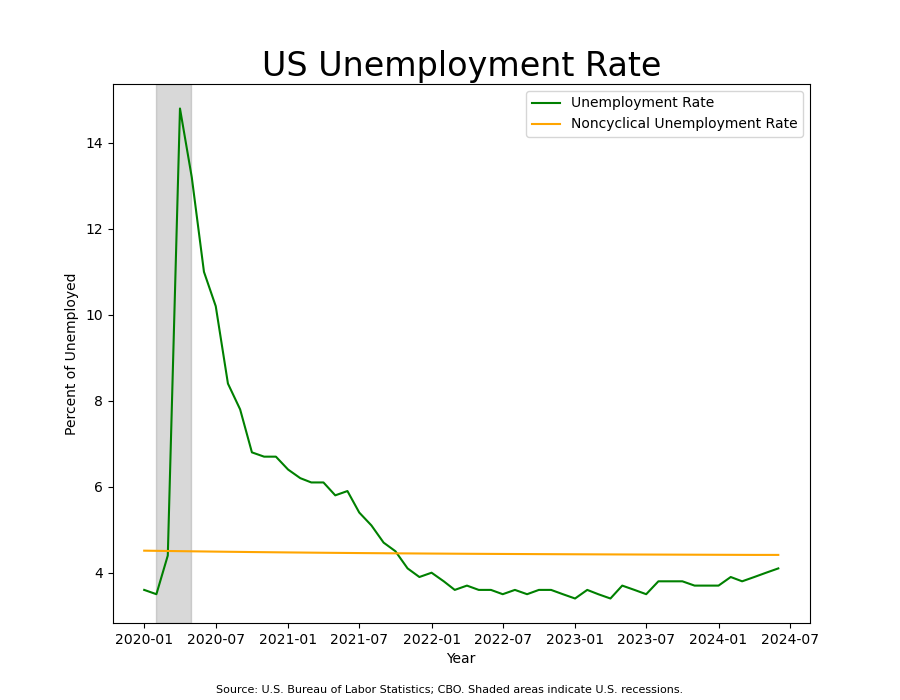

The Unemployment Rate increased by .1%, and remains below the Noncyclical Rate, indicating that the labor market is still tight.

Given where the unemployment rate is relative to the natural rate, there doesn’t seem to be much cause for alarm; however, as we discussed last week, rates of change are more important than levels, and the labor market can quickly transition from full employment when corporate profit margins are squeezed—as is the case when corporations can no longer count on passing along higher prices to their customers (i.e., disinflation).

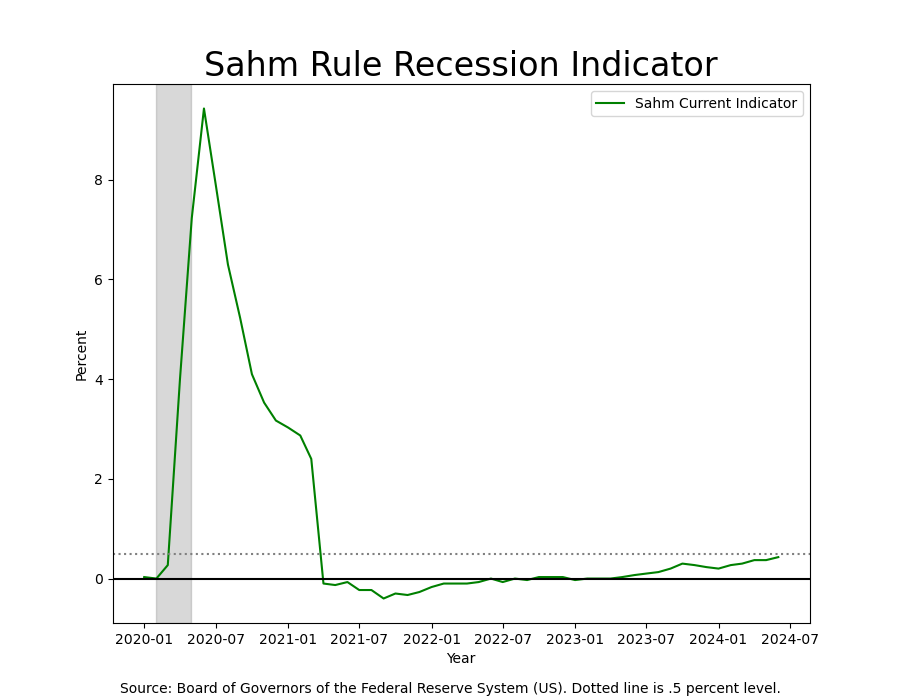

Former Federal Reserve economist Claudia Sahm is credited with identifying an empirical regularity (not a law, but an observed property) that has an impressive track record in identifying inflection points in the economy. The resulting regularity is referred to as the ‘Sahm Rule’, and when it is observed, the economy is likely already in recession. If the Unemployment Rate were to increase a mere .1%, it would exceed the critical threshold and signal that recession has already begun.

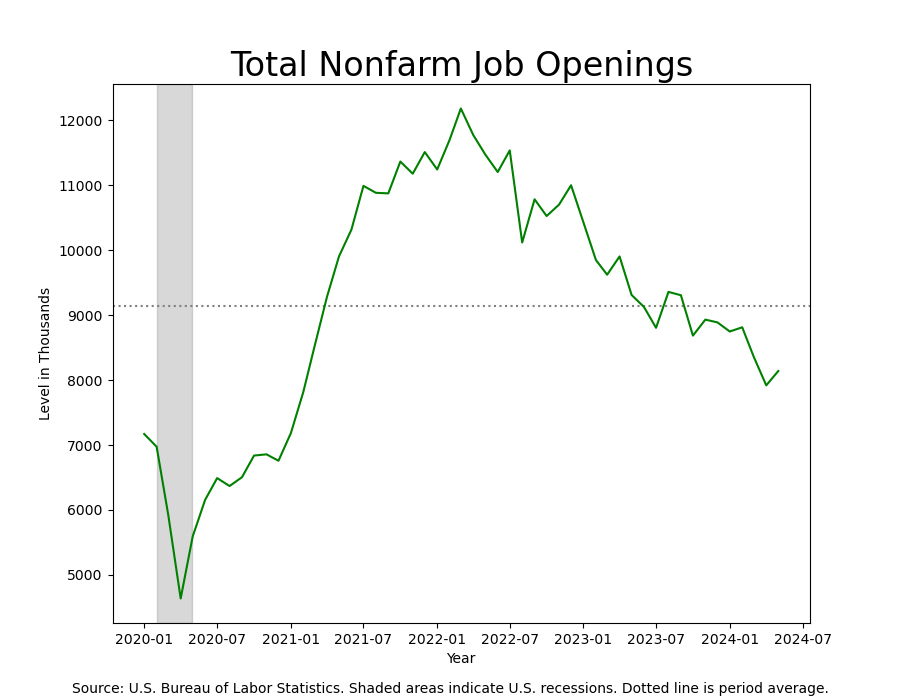

For statistical reasons that are too complex (read: boring) to get into here, we believe that it is unlikely that the US economy is on the brink of recession. Furthermore, other indicators (detailed hereafter) lead us to believe that the economy is still robust and unlikely to tip into recession. But it is important to note that the softening of the labor market has quickly progressed. For example, Job Openings, a measure of demand for labor, are substantially off their post-pandemic peak.

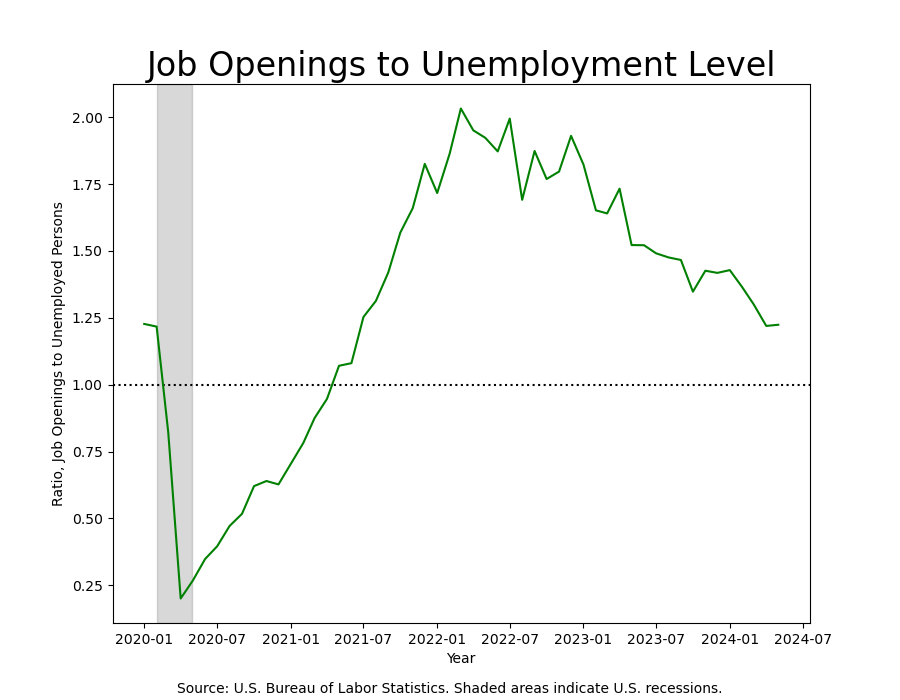

Combining this measure of the demand for labor with a measure of supply of labor (as measured by the number of unemployed), we can derive a ratio that indicates how well supply and demand are balanced in the labor market. A reading of one indicates perfect balance, whereas a reading above one indicates labor market tightness. This ratio currently sits at about 1.25.

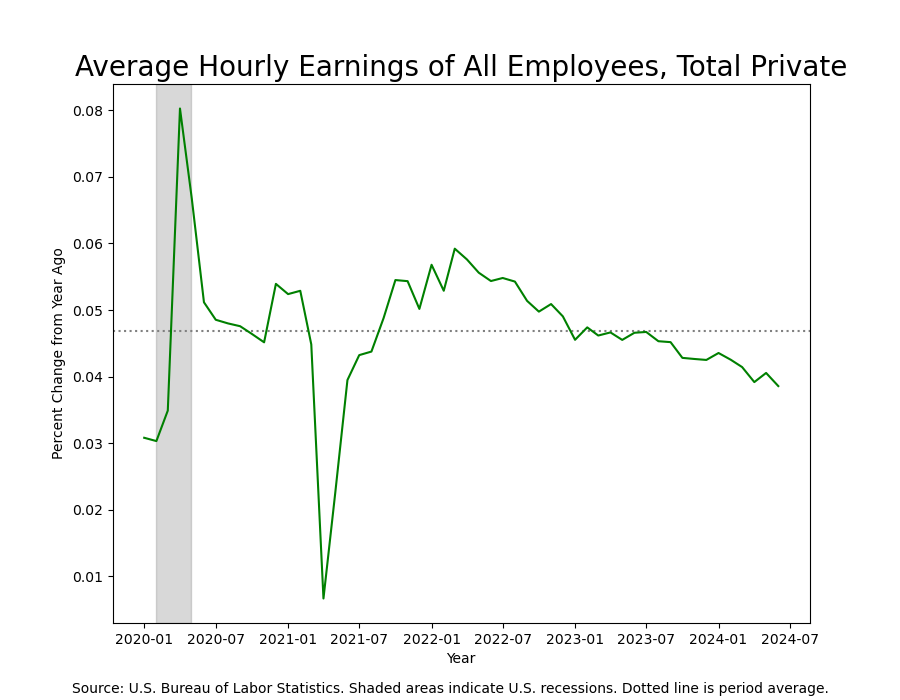

The downward trend portends a labor market approaching equilibrium. If this is true, then we should observe the wage rate (the price of labor) to be falling. And that is in fact what we do observe. Average Hourly Earnings, our measure of the wage rate, continues to drop off. This relieves cost pressures on corporations and has been one of the more worrisome drivers of sticky inflation over the post-pandemic period.

Last time we concluded with a chart that compares the inflation rate as measured by Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) with the Unemployment Rate. The chart is valuable because it combines in one place the dual mandate with which the Federal Reserve is charged: to ensure the stability of the general price level, and to promote full employment.2 As we predicted last time, PCE came in lower at 2.6%, indicating further progress against inflation.

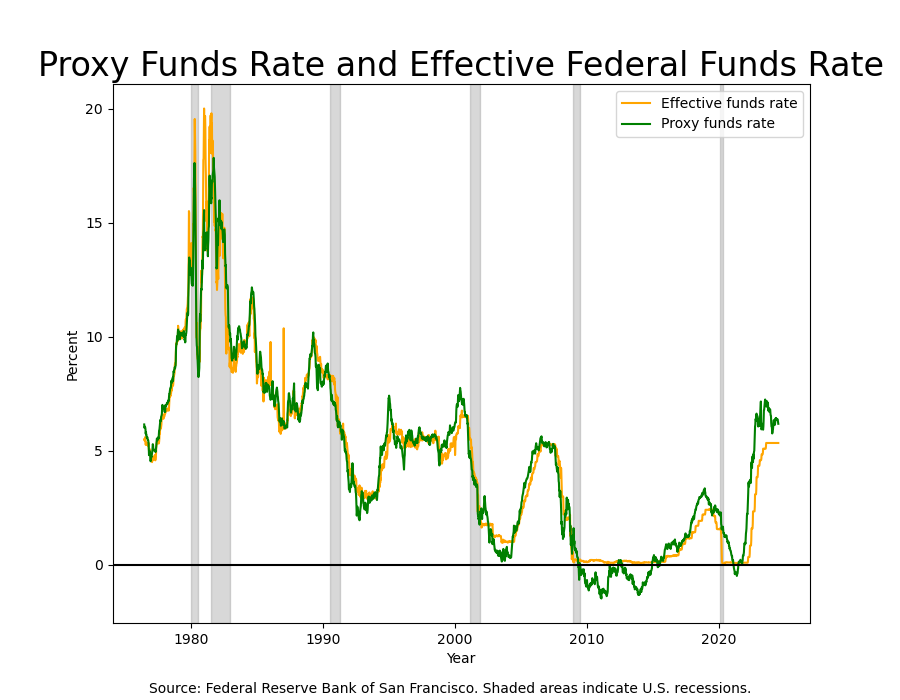

Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve Chair, appeared before Congress for his bi-annual hairshirt-and-flagellation tour, and stated that the FOMC is attentive to the shift in the balance of risks: that there is now more downside risk in the labor market; and that the downside risk in the inflation rate is subsiding. While the FOMC may not yet have enough evidence to confirm its view that inflation has resumed a downward drift, it cannot be far from it. Thus, the anticipation of interest rate cuts beginning in September.

St. Jerome the Dilatory

Given that prices are heading in the right direction, and unemployment is not, it seems to us that the time is nigh for the Fed to begin to reduce the policy rate to head off rapid labor market softening at the pass. Financial conditions have relaxed somewhat since the spring but remain far too tight to support continued expansion as demonstrated by the reduction of activity in the Long Economy. Sooner or later, what happens in the Long Economy dominates what happens in the Short Economy, and that point is rapidly approaching. The Fed will likely wait until September to cut rates, but it is unclear whether that will provide enough time to arrest the cascade of negative effects that a too-loose labor market engenders.

‘Delayer’

Setting aside the unofficial third mandate, stability of the financial system.