Fortunate is he who can learn the causes of things,

And to subject beneath his feet all fear and the inexorable doom

Of the greedy river of the land of the damned.

- Virgil, Georgics II.490-2

Almost nothing is known about the Roman Philosopher-Poet Lucretius, who lived and died in the first century BCE, except that he had a patron, Memmius, to whom he dedicated his only extant work, De Rerum Natura. It is a stunning poem of several thousand lines of dactylic hexameter, the meter used for writing epic poetry. That this admirable work extolling the virtues of Epicurean philosophy was composed in the same poetic register as the Iliad and the Odyssey reveals that Lucretius believed his project of seeking the truth behind natural phenomena to be comparable in achievement and honor to the heroic exploits of the Homeric heroes. In this way, Reason is the hero of the intellectual epic, and it is through the acquisition of truth one might, as Virgil writes a half-century later, release oneself from anxiety and the fear of death1.

A concept central to the physics of the De Rerum Natura concerns the behavior of the indivisible (atomic) particles that make up the universe. These operate according to fixed, immutable laws that prescribe their behavior: to fall, ever downward, into the void. However, if the world consisted only of atoms moving in one direction, then they would never collide and produce through their interactions with each other the natural phenomena we observe in the world with our senses. Therefore, a random swerve factor, the clinamen, is responsible for breaking up the quantum monotony and injecting variety into the universe.

The US economy largely continued where it left off in the fourth quarter with weakening, but still strong consumption and investment. The injection of uncertainty into trade policy and—yet to be introduced but coming soon nonetheless—fiscal policy has knocked the economy off of its course of steady expansion. We have yet to observe the effects that this deliberate introduction of unpredictability into the economy will ultimately have, but we can already see small collisions occurring in the billions of tiny interstices in its perturbed fabric.

Income

Real GDP fell in the first quarter of 2025 to -.3%. That it was lower from the fourth quarter of 2024 was not a surprise, as the market expected lower GDP due to political uncertainty. Our econometric model suggested a more modest decline to .5%, but remaining positive. At -.3%, the economy is running approximately 2% below potential growth. This isn’t a train wreck, and we have experienced quarters and consecutive quarters of contracting growth from time to time without recession. The most recent of these was during the first and second quarters of 2022, which was the direct result of sudden and swift increases in interest rates. (Not the Fed’s increases, but rather the market’s.)

The swing to economic contraction was due in part to an increase in goods imports as businesses and consumers raced to beat the imposition of tariffs over the past three months.

GDP measures the value of things produced in the economy, and so to avoid counting foreign-produced goods and services in the calculation, these are removed. This is a matter of measurement, not of trade competitiveness: every dollar spent on imported goods would not necessarily have been spent on domestic ones instead. However, some US production may have been deferred and that earmarked capital diverted to purchasing imports instead in order to keep the overall costs of production lower under the assumption of higher future tariffs.

To get a better picture of the health of the US economy, we can use the inflation-adjusted level of expenditure by domestic private sources, or Real Final Demand. This is sometimes referred to as ‘Core GDP’, as it gives a better signal-to-noise ratio for aggregate demand. As measured by this metric, the economy is holding up, though certainly running below its longer-term average.

Business Fixed Investment is running below average, reflective of the general environment of uncertainty, but is still positive. While consumer spending accounts for 70% of economic activity in the United States, the business cycle is driven by businesses’ response to consumer spending. If businesses think consumers will keep spending, then they will invest in productive capacity to meet the expected level of demand; and if not, they won’t. While we’re awaiting April data on Business Fixed investment, we can see that businesses in general continue to spend, though at lower levels than you would expect going into the New Golden Age.

While Business Fixed Investment is running below average but still positive, plans for the future have changed. What had been a general enthusiasm for capital expenditure has turned. The Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia, New York and Dallas surveys all showed reduced intentions on the part of businesses to make investments in productive capacity.

In a positive sign for workers, personal income adjusted for inflation is growing at an above average rate. Since unemployment is so low, this is to be expected.

Unfortunately, the above-average increase in Real Personal Income isn’t currently matched by similar growth in Real Disposable Income. So, taxes are taking an ever-greater share of the gains workers are making.

Prices

The Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of price inflation, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, showed moderation toward the Fed’s policy goals this month. Both the headline number as well as the core number showed no change in the price level in March.

While no change in the price level for the past month is welcome news given the higher reads we’ve seen in the last several years, that also means that inflation remains about .3% and .6% above target, respectively.

The Federal Reserve prefers the PCE to the not-fatally-flawed Consumer Price Index (CPI) and uses core PCE for market determined prices most. This measure is free of the imputed prices that statistical agencies include to approximate change in hard-to-observe prices. Like the PCE and Core measures, these show inflation still higher than target.

The broadest measure of price change we have is the GDP Price Deflator, which gets released quarterly along with GDP. At more than 5,000 items in its basket, it is by far the broadest measure of price change we have. However, being quarterly, it is not as frequent and sometimes tells us more about where we were than where we are headed. Those caveats aside, the GDP Implicit Price Deflator showed an uncomfortably high 3.7% increase in prices.

Retail and Consumption

As we mentioned earlier, Personal Consumption accounts for nearly 70% of economic activity in the United States. Consumer appetite can wax and wane on a month-to-month basis, so we smooth these out with moving averages. The three month-moving average shows that Personal Consumption is running below average but hasn’t slipped into contraction. The American Consumer seems to have found a lower gear.

Labor

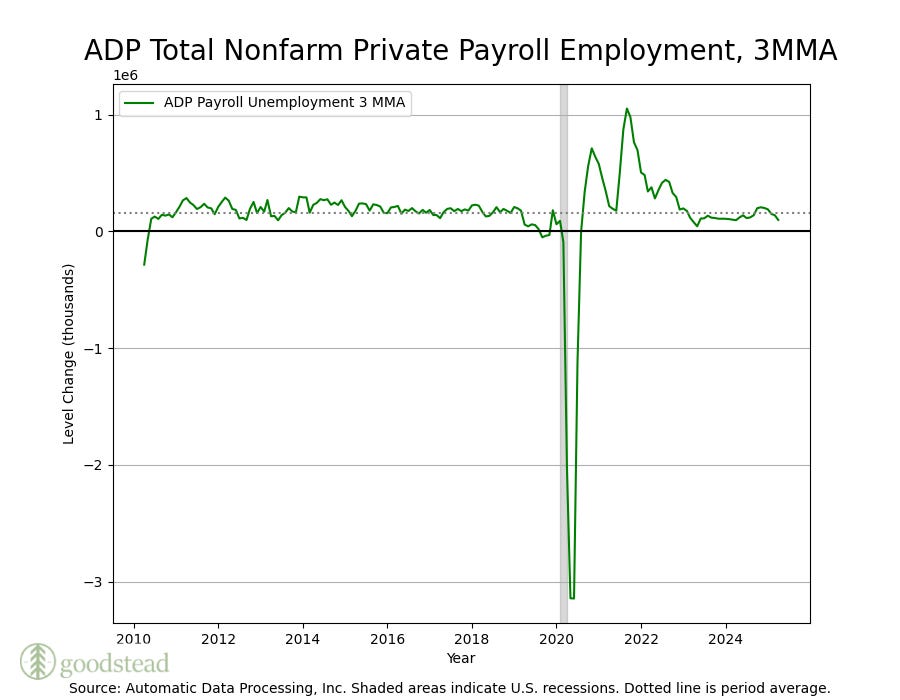

We received mixed signals from our two payrolls data sources this week. First, from ADP, the provider of private payroll administration to businesses, showed a dramatic slowdown in new hires: 62,000 new employees in April, down from 147,000 in March and far below expectations of 110,000.

Meanwhile, the Government’s numbers were much better at 177,000 new hires in April, beating consensus estimates of 130,000. The number of hires was slightly down from March, but this was considered a good report, as it was better than ADP and is consistent with an expanding economy.

The Participation Rate was essentially flat, though slightly higher.

The Unemployment Rate held steady at 4.2%. The US economy remains at full employment.

Job Openings were lower again this past month. Employers are taking down job postings as they await certainty on tariffs and consumer demand.

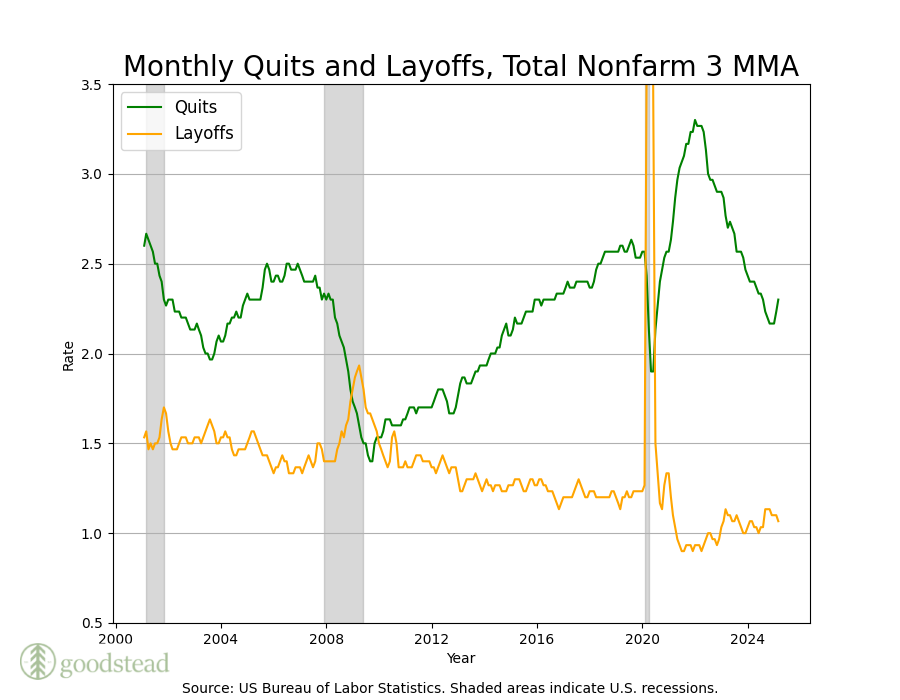

Comparing balance between demand for labor and supply in the labor market, we see that the market is moving toward equilibrium—though the rate at which it is moving suggests that it will overshoot, lending capital leverage in setting wages.

In something of a surprise, however, Quits were up and Layoffs were down. We’d expect the opposite given the apparent softening of the labor market.

Changes in the employed population haven’t yet been dramatic enough to signify a self-reinforcing downturn.

States run Unemployment Insurance programs, so requirements vary from state to state as to when workers are eligible to file claims. We do see that historically a rise in initial claims only really gets moving once claims pass their longer-term average. For this reason Initial Claims is a lagging indicator of economic contraction. So, absent an exogenous shock, the US is nowhere near that trendline as of right now.

Continued Claims similarly have risen but are not high. Because these are lagging indicators, we keep an eye on the hiring rate to anticipate turns in the economy. Looking in the rearview mirror, we can see that we’ve generally had a labor market that has been pretty good at getting people back to work.

Surveys

Switching from Optimism to Pessimism, we can wee that Manufacturing Employment is in contraction. It’s a good thing that Americans don’t particularly want factory jobs because there aren’t any new ones on offer.

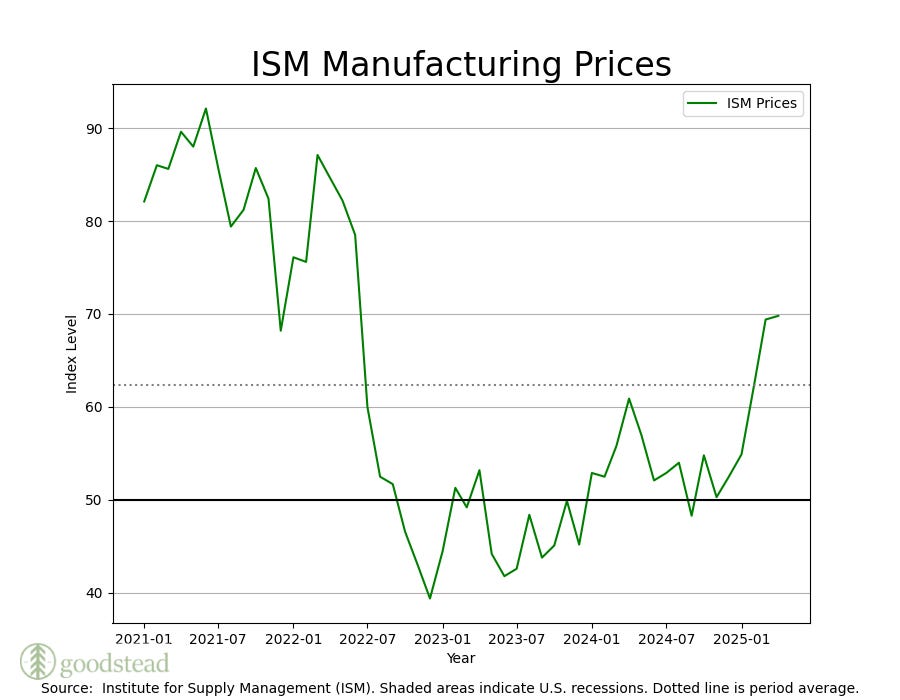

Prices for inputs to manufactures are increasing as well, likely in response to tariffs or the anticipation of tariffs. These price increases take a few months to flow through to consumers.

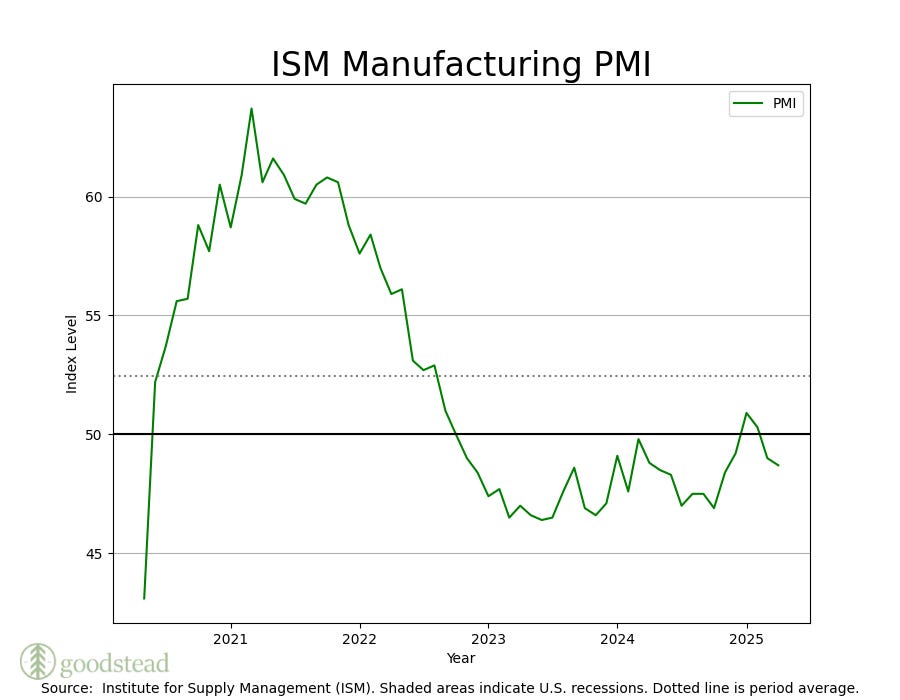

The Purchasing Managers’ Index shows that orders are in contraction. Businesses are in wait-and-see mode.

Housing and Construction

Construction Spending continues to fall. This is consistent with business’ plans to reduce capital expenditure in the coming months, as well as the slowdown in the housing market. While not a hugely important part of the US economy, it is a highly cyclical one, so it is important to gauge. Whether or not American can still build stuff, American isn’t building stuff right now.

Manufacturing

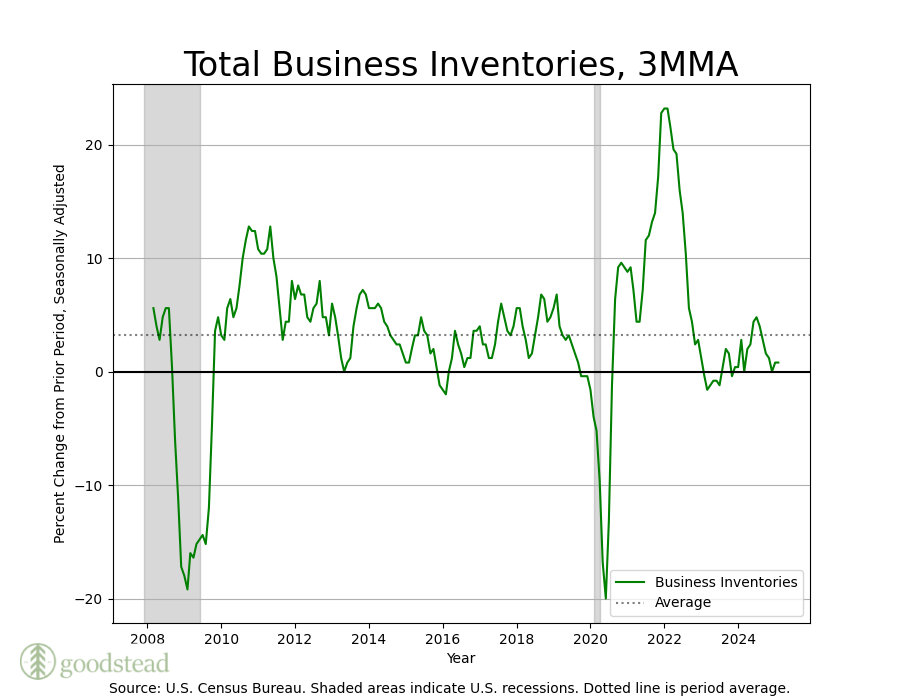

Inventories are pretty low and are likely to stay here for a bit.

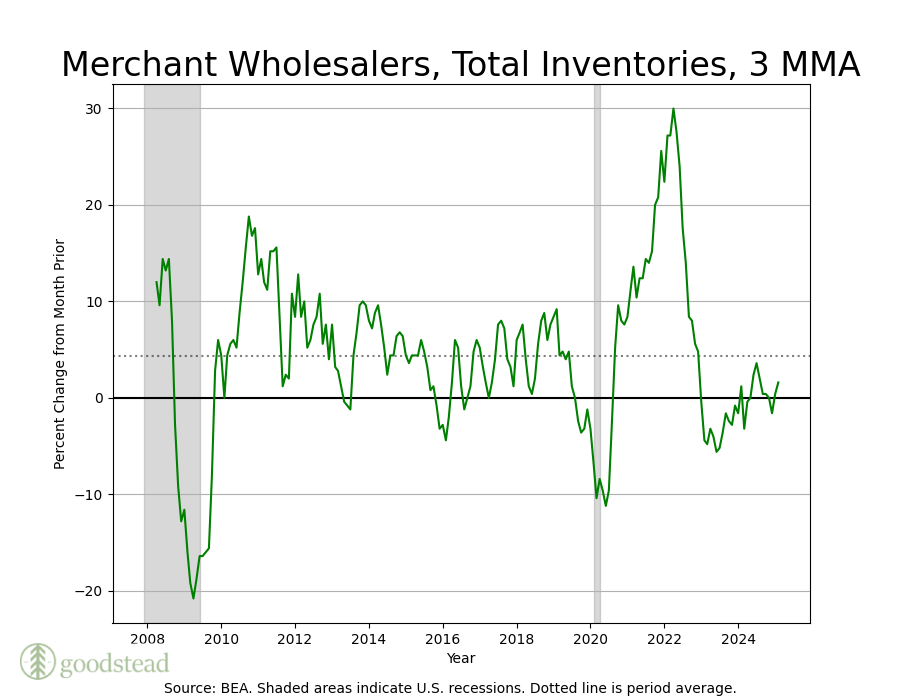

Wholesalers are also likely holding off on building inventory until the uncertainty over the tariffs they face on imported goods has passed. Part of the problem with blanket tariffs is that it didn’t make sense for businesses to look for countries other than China to import from, since all countries faced draconian tariffs. Although tariffs on other countries have been relaxed, the tariff rate is much higher today than it was on April 1. And because the current administration isn’t known for its will of iron, they may be delaying importing and building inventory today out of the expectation of lower tariffs tomorrow.

In Sum

The US economy is a massive and dynamic complex. It continues chugging along in much the way it did in the fourth quarter of 2024, so not much has changed despite the change in administration. Part of this is undoubtedly due to the fact that it takes time for policy changes to have impacts in the real world. So it will still take time to see how policy changes will affect the economy. It is not necessarily the case that the ‘Vibecession’ hasn’t rebounded on America, and that bad feelings won’t come to mirror economic data. That said, the preponderance of data points toward further slowing in the economy. We can see from falling sales at sellers of inferior goods and services that the bottom 20% of the economy is now struggling. Harder days remain ahead for those who are the least equipped to manage them. But the broader economy does seem to exhibit resilience for now. Whether that statement pertains in the next quarter will be a matter of whether the administration is chastened by the cold reception its policies have received in the financial markets.

Share this post