Well, that went poorly. Our apologies for the hiatus. Between the end of the school term, onboarding new clients, portfolio adjustments necessitated by the election, and finally the holidays in America, we couldn’t find the time to scribble a letter. Look for our regular weekly missives this year, and a daily chart to help you keep your head above the fray.

So, in the eleventh year they set out from Eretria and returned home, and the first place in Attica they took was Marathon. And while they bivouacked in this place, partisans from the city arrived and others from the country flowed to them—to those for whom Tyranny was rather more preferable than Freedom.

—Herodotus, The Histories 1.62

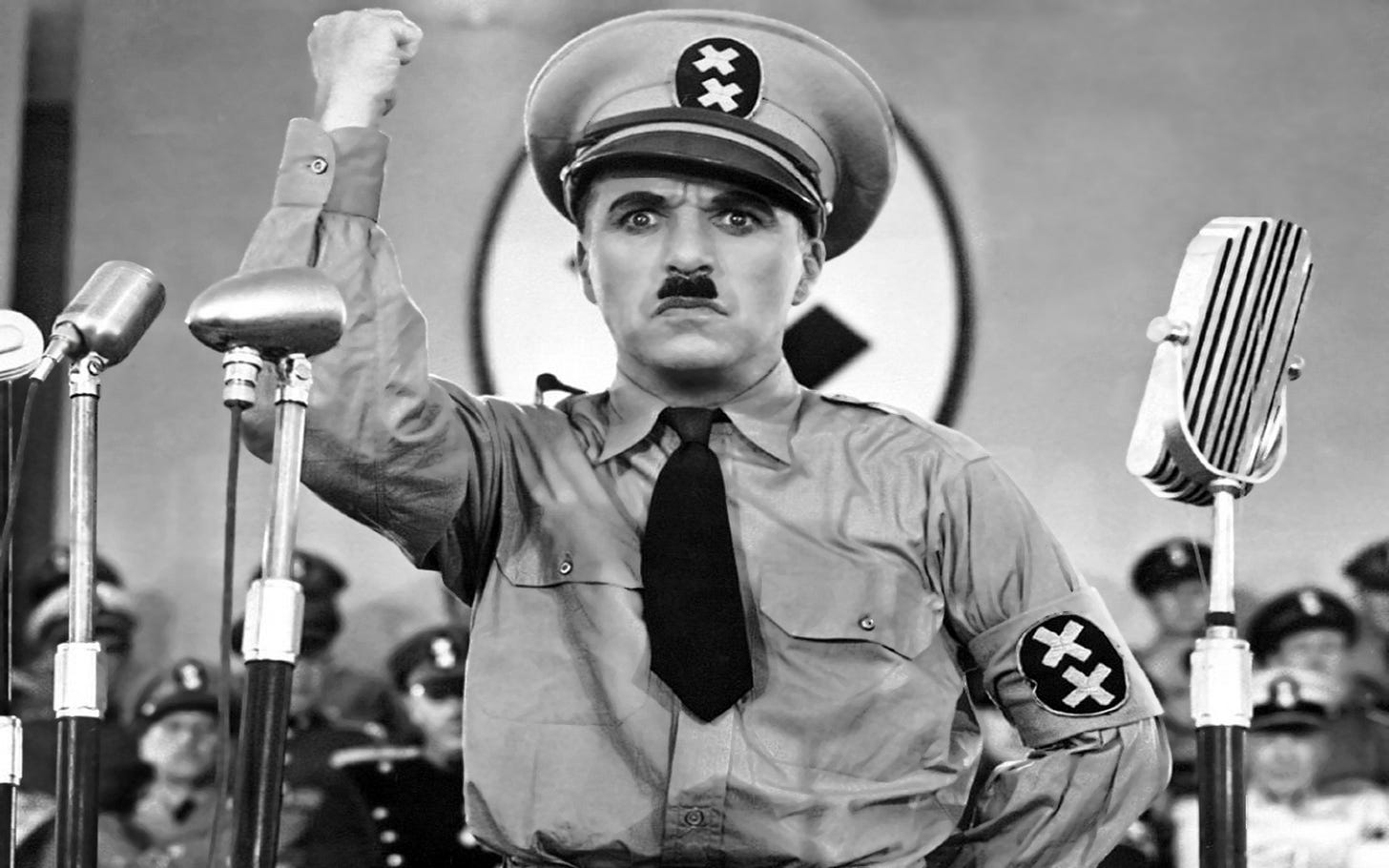

American Tyrant

Pisistratus, the 6th century BCE three-time tyrant of Athens, first came to power by feigning victimization at the hands of his enemies. Having purposely wounded himself and his horses, he rode into Athens demanding armed protection from his foes. He then used his bodyguard and popularity with the poorer citizenry to seize power and effect his first one-man rule. Five years later, he was exiled as the result of the cooperation of his political rivals and fled the city.

Reconciled to one such rival a few years later, he returned to Athens and to power, legendarily accompanied in his chariot by a tall woman dressed as the goddess Athena.1 He immediately broke his promise of an agreed union with his rival’s daughter, purportedly out of favor for his sons whom he intended to carry on his political and economic legacy rather than the issue of this new matrimony. Another forced exile ensued, and Pisistratus decamped to the countryside where he amassed extraordinary wealth from farming and the mining of precious metals.

His newly minted wealth enabled him to hire a private army and—counting both the collusion of Athens’ great rival, Thebes, and the favor of the poor yeoman farmers of Attica’s hills, the Hyperakrioi, among his assets—march south to confront a citizen force that had been arrayed to confront his coup. With the aid of a timely prognostication, and perhaps a bit of luck, the coup succeeded, and Pisistratus enjoyed his third and final term as tyrant of Athens.

The classical historians aren’t unanimous as to the quality of Pisistratus’ tyranny, but some good as well as bad seems to have emerged during his rule: the establishment of regionwide games and cultural events2, the recording of the Homeric epics3, the rationalization of agricultural policy, and the promotion of trade; these were supposed to have occurred alongside property expropriation, political repression, cronyism and self-dealing. His death in office was followed by the assumption of power by his sons, one of whom was assassinated (Hipparchus), and the other of whom (Hippias) engaged in a paranoid program of political killings before being exiled. Ignominiously, he would later find refuge in the court of Darius, the Persian Emperor, and guide the Persian armies to their defeat at the battles of Marathon and Plataea in the Persian War.

Yet two critical changes came about as the result of the tyranny of the Pisistratids: the first, Ostracism, allowed for the expulsion of citizens thought to be a threat to the democratic rights of the citizens of Athens, thus replacing the use of violence to counter threats to the body politic; and the second, Democracy, imbued both elites and commoners with equal political power.

We won’t write much about the political implications of the election. That’s terrain better trammeled by others with the requisite expertise. We can opine on ramifications for the markets and the economy, though, which we shall do in broad strokes further below. But we should note that sometimes it requires a Pisistratus to give rise to a Cleisthenes.

We begin the New Year as we do every year with a review of the performance of the Global Market Portfolio. Then we’ll check in on the most important thing: what’s priced in for 2025. We’ll conclude with a few thoughts on longer-term trends and what to keep an eye on over the coming year.

Diversification is for Suckers

For the second year in a row, the Global Market Portfolio underperformed the S&P 500 as well as the Standard (US) Portfolio of 60% equites, 40% bonds. Of course, the performance of the S&P 500 has been historically good and is responsible for the Standard Portfolio’s outperformance. US Fixed Income lagged badly and offered little in the way of diversification benefit.

The first three quarters of 2024 was a great time to take what the market gave you, as nearly all asset classes were up. In the fourth quarter, US growth assets took off and left everything else in the dust. If it was denominated in USD, and it had equity or equity-like exposure, it paid to hold it.

The picture that emerges is of a world that changed from the end of the third quarter to the end of the fourth: growth will be US Equity-centric, USD-denominated, and Global Fixed-Income phobic.

The markets have fully embraced US exceptionalism as demonstrated by these changes in marks and are pricing in rapid growth—as well as its necessary consequence, higher rates of interest. Whereas the dominant question in 2024 was whether interest rates would remain elevated for a period of time longer than the market had previously thought likely (“Higher for Longer?”), now the question for 2025 seems best paraphrased as “Higher Forever?"

The View from 2025

Markets are discounting machines. Taking all readily available information, they compute a money-weighted average of the expectations of everyone in the markets and apply it to things for sale. They are forward-looking and so attempt a truly impossible thing: to tell the future. While the mechanism itself is a well-oiled machine, the expectations it incorporates into these forecasts are hopelessly tainted by an irreducible subjectivity born of human sentiment and folly.

It is instructive, therefore, to examine what the market believes the future will look like so that we can question whether the sum of expectation yields a rational result. We can use a number of methods to determine whether these consensus opinions are indeed sensible, such as historical comparison and fundamental analysis, but we should not expect these methods to provide us with a ‘right’ answer, or even a conclusive one. But this is a necessary exercise, as we know that the market is often wrong, and if we do not make a judgment about whether it is right or wrong, we must share in its fortune, for better and worse.

Plotting the futures prices for select instruments, we can get a picture of what the market is discounting for the year ahead, and it confirms that the aggregate opinion is for current trends to continue: investors will continue to pay higher prices for growth, providing a more than 12% return for the largest non-financial companies in the United States; a continued 5% appreciation for gold; further deterioration in bond yields and a slight worsening of short term yields; only modest growth for the broader US equity market at 2%; the dollar flat; and oil to lose 5% over the course of the year.

This, of course, is not shocking: the best predictor of where a random walk’s next step will land is the current position of its last one, plus some drift factor that accounts for its trajectory over time—and for equities, as we have seen for the last two years, that trajectory is, ever and unceasingly, up. Even the large drawdown equities suffered in the fall of 2023 was but a brief interlude in its heavens-mounting ascent.

With the exception of growth-y equities, we find justification for current pricing. US GDP growth should sustain current elevated levels, as infrequently-precedented tides of fiscal stimulus, paired with extraordinary business capital expenditure and consumer spending, combine to keep growth unusually high. Price-to-earnings multiples for the darlings of the retail crowd, however, cannot be countenanced at present given what we know about the current state of AI and the barriers it faces to its adoption and monetization. We expect the productivity increases the US has been witnessing since before the pandemic to continue, as these are likely due to implementation of more mundane technologies such as labor-saving robots and workflow automation. These ought to benefit the S&P 493, mid- and small-cap, as well as value stocks.

Yields should continue to climb above 5%, as the fiscal posture of the United States continues to sag. Short rates will remain around 4% in response to the inflation-engendering actions of the new administration: mass deportation, constriction of skilled and unskilled immigrant labor pools, imposition of import taxes, among others. Oil should be lower on increased supply—which, we should note, is already ample. It is unclear to us whether producers are likely to bring on additional capacity at the current price level no matter what restrictions on new leases are removed. Looking beyond the United States, stock markets in the developed and developing world are priced attractively and are poised to rebound from recent pessimism. Investors who buy these markets with extravagantly priced Yankee Dollars, we believe, will outperform US equity markets on both a risk adjusted as well as an absolute basis.

Predictions, Especially About the Future

Our regular readers know that we are reluctant to offer predictions, especially about the future. Who lives by the crystal ball will gnash teeth on shattered glass. In the present circumstance, we feel more comfortable in presenting an opinion, as we have recent and relevant analogs from which to draw likely scenarios. For the Americans’ most recent decision to re-elect Donald Trump to a second four-year term is reminiscent to us of no other event more than the United Kingdom’s fateful decision to leave the European Union.

By leaving the EU, the UK erected barriers to trade, for leaving the customs union without trade agreements in place had the effect of imposing tariffs—taxes—on all its trade. It also ensured that its major trading partners immediately erected retaliatory barriers against all of its exports, since leaving a customs union without a trade agreement in place had the effect of immediately reducing its competitiveness. Additionally, the wage rate immediately increased as the UK could no longer depend upon the less expensive labor of its newly arrived immigrants and EU-based guest workers as part of its labor force. The combination of these factors was a reduced growth impulse as well as an increased inflation impulse, which resulted in an immiserated citizenry that now faces the twin specters of higher borrowing costs as well as lower growth with which to service its increasing debt load.

While we believe that the United States will likely see higher rates of inflation and lower rates of growth as a result of its Amerexit, there are other, more chilling results of its choice to withdraw from the world: the loss of the world’s foremost sponsor of freedom and democracy, its promulgator of the rules-based international order, and the sole guarantor of free and fair global trade. This makes the world a more uncertain place. As we have written before, the third global factor which influences asset pricing, volatility, is synonymous with uncertainty; we know that asset values are sensitive to volatility, and that when volatility is high, asset values fall, just as they rise when volatility is low. The impulse from volatility is now getting priced into US stocks, but has a ways to go. International stocks have already priced in higher volatility, so there the risk profile is asymmetric to the upside.

Investors in developed markets tend to focus only on growth and inflation, the two other primary factors, and the only ones that repay attention in law-based societies. This reflects the victory of the Technocracy. In emerging and frontier markets, however, time and again regime stability proves that it is the most important factor to consider. As America indulges in its Emerging Market tendencies, it leaves itself susceptible to Dutch Disease4 at the same time that it leaves vulnerable those countries which most benefit from the Helsinki Convention’s protection of the rights of smaller countries. It weakens itself within and weakens its allies without. Were it not for the comparative weakness of Russia and China, the world would indeed be a much more dangerous place. The whole world, and not just disaffected Americans, will look longingly to some future Cleisthenes for their deliverance.

Whether the Athenians were fooled by Pisistratus’ dea in machina, or the display merely evoked their enchorial reverence for the demonym-granting goddess, is unclear.

The Panathenaic games and the Greater and Lesser Dionysia

The Iliad and Odyssey

The relationship between the focus on a given sector or industry at the expense of the development of others. We often see this in emerging countries whose extractive resource-centric economies prevent them from focusing on human capital development, which is necessary for prosperity and human flourishing in the long run.