Step into my wayback machine and I will take you to a place BCE (Before the COVID-19 Era) called 'the Nineties'. The Wikipedia entry sums this time up pretty niftily:

The 1990s are remembered as a time of strong economic growth, steady job creation, low inflation, rising productivity, economic boom, and a surging stock market that resulted from a combination of rapid technological changes and sound central monetary policy.

It's quite reminiscent of the current era, not least of all because of the large number of its fashions currently gracing our streets. The US economy is firing on all cylinders--which idiom will be obsolete in ten years but had currency during the time under examination. Yet, it pretty fairly describes what we see in the data: broad-based growth, low unemployment, falling inflation. And while the economy has been pretty good--actually, extremely good--consumer confidence had been in the doldrums. Not too long ago, the University of Michigan survey of consumer sentiment was dramatically lower, on par with the worst episodes since its introduction in 1966. In fact, at one time it was lower than even during the stagflationary 1970s. Now we see a recovery in sentiment to levels not inconsistent with economic expansion. The chart below shows the rapid recovery in sentiment over the past two months.

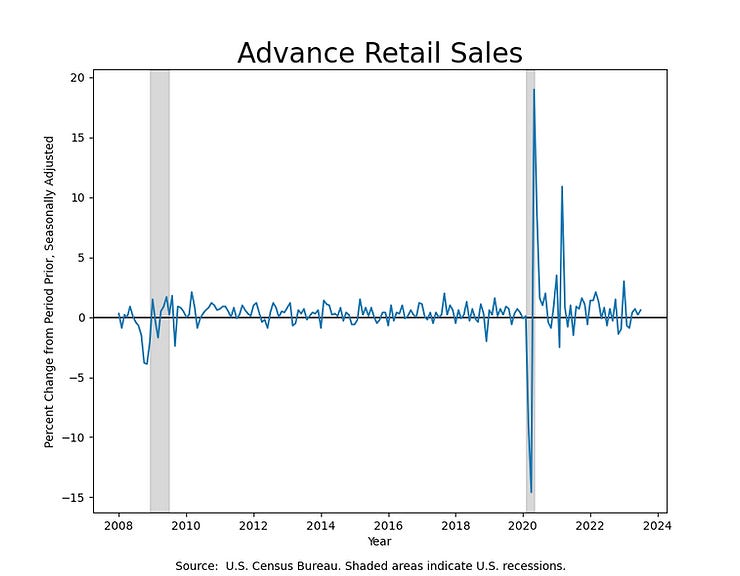

This is similarly reflected in the strength in Retail Sales we highlighted last week. When consumers feel comfortable about their economic prospects, they open their wallets.

As might be expected, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), our most important indicator of economic activity, as it reflects whether the economy is expanding or contracting, registered a healthy rate of growth in the fourth quarter of 3.3%. Compare that to the historical average of the last couple of decades, where US growth averaged about 1.9%. Growth for 2023 was a solid 2.5%, a full half-a-point higher than that same average--and when you're talking about GDP, half-a-point is a lot.

As of this morning, our econometric model forecasts growth for the first quarter of 2024 to continue at a pace of about 2.4% for the foreseeable future.

Since inflation continues to fall, and growth is strong enough to sustain the current high level of employment, we still do not see the Federal Reserve cutting interest rates at its March meeting. Since we last wrote, the market-implied probability of an interest rate cut at the Fed's March meeting fell from 80% then to 50% now. Even though the odds of a rate cut are now even, we maintain our opinion that rates will remain where they are until and unless the data suggest otherwise.

We don't want to extend the analogy of the 20's to the 90's any further, since so much has happened in 30 years. Suffice it to say that the decade similarly proceeded under higher rates (averaging 5.15% over the decade) than the decade leading up to the current decade ACE. It may be that rapid technology change accommodates, or requires, higher interest rates.

The Third Global Factor: Regime Stability

Volatility and Its Permanent Place in the Standard Portfolio*

Nearly all financial assets derive their return from the Economic Growth factor. Modern Portfolio Theory holds that it is possible to reduce the volatility of the standard investment portfolio while contributing to its return by the addition of uncorrelated return streams, even when those returns are more volatile than the portfolio itself. To build a diversified portfolio, it is necessary to include assets that do not depend upon Economic Growth for return. It is thus that the inclusion of Commodity Trading Advisors (CTAs) and Global Macro Managers, who employ momentum strategies that do not depend upon economic growth for their return, improves the Sharpe ratio of the Balanced Portfolio. Volatility strategies warrant inclusion on the same basis.

The 60/40 “Balanced” Portfolio and Its Limitations

The standard 60/40 equity/fixed income “Balanced Portfolio” derives 99.7% of its risk from its equity exposure —which is to say, a derivative of economic growth. This concentration of risk ensures that the portfolio is highly sensitive to fluctuations in the business cycle. Since the 1960s, investors have depended upon an allocation to fixed income to provide downside protection against falls in the prices of equities due to the observed low correlation between equities and fixed income.

The long-term correlation of the S&P 500 and the Bloomberg (formerly Lehman) US Aggregate Bond Index is .225—uncorrelated, certainly, but positive in its relationship. To use the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index to hedge the risk of the S&P 500, one would employ a hedge ratio of -.63: for every unit of equity exposure, one would add -.63 of fixed income exposure to hedge it, resulting in a portfolio mix of ~61% equity to ~-39% fixed income.

If the correlation were negative—as it sometimes is—then a portfolio that consisted of long positions in both equity and fixed income would behave in a desirable fashion and yield a balanced portfolio: the fixed income allocation de-levers the portfolio, and presumably, the credit and recovery risk exposure diversify it. Even so, a correlation coefficient of .225 is an R2 of .05, and so not at all an effective means of hedging equity risk.

However, the correlations of equity and fixed income are not stable over time, as there is no universal law that mandates that creditworthiness and recovery rates move independently of corporate earnings. That interest rates have often fallen when corporate earnings have, and similarly risen along with corporate earnings, are mere artifacts of regimes in which contemporaneous inflation rates traveled concomitantly with economic growth.

This is why the hedging property of fixed income is regime-dependent, and the relationship only holds true in certain growth, inflation, and political stability regimes. Toward the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, growth fell, inflation surged, and political instability increased. As both equities and fixed income are negatively impacted by falling growth, rising inflation, and regime instability, the negative correlation between equities and fixed income broke down. Consequently, the traditional 60/40 allocation experienced a significant drawdown in 2022.

With the Dot-com bubble’s collapse in 2002, institutional investors, perhaps stung by their irrational exuberance, looked to find alternative sources of risk that would provide return during troughs in the business cycle. This marked the rise of the so-called “Alternative Asset” classes, specifically Hedge Funds and Private Equity, which were thought to provide uncorrelated returns as well as greater downside protection. This new dogma tested its adherents’ faith during the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and was found wanting; the correlations of all risky assets converged, and the much-vaunted benefits of diversification disappeared just when they would have been most useful.

Following the GFC, the following twelve years of alternative asset returns proved disappointing as placid markets failed to provide the price dislocations necessary to make trading schemes profitable, and ever-larger private equity transactions consummated at ever-higher valuations spelled ever-lower internal rates of return. The extended period of low-interest rates and quantitative easing provided strong tailwinds to long-only, growth-focused equity portfolios, and a combination of uninterrupted upward momentum and low volatility produced a high Sharpe-ratio trade for the ages. Investors were punished for discipline as diversification went unrewarded.

The COVID-19 Pandemic presented new challenges to the Balanced Portfolio. Risky assets fell suddenly and sharply in response to this new exogenous shock, then immediately recovered as expansionary fiscal and monetary policy combined to provide support both to the real economy and financial markets. The subsequent reflation in risky asset valuations saw equities resume their long march uphill, and diversification once again proved to be a millstone about the neck of the 60/40 portfolio: developed market real bond yields, already low by historical standards, went negative in many markets as zero-lower-bound interest rate policy, Charybdis-like, pulled them underwater.

As persistent and progressively broad-based increases in the general price level spurred Central Banks to shift monetary policy from an accommodative to an aggressive posture, the rise in interest rates pummeled growth equities and long-duration fixed income alike, and the 60/40 portfolio was revealed to be severely unbalanced, posting drawdowns comparable to a straight equity allocation. Over the two years of COVID-19-related market action, the Balanced Portfolio had exhibited bond-like upside and equity-like downside. Not only did diversification go essentially unrewarded, but its performance suffered more as the degree of uncertainty increased. It had been exposed as fragile.

What We Would Actually Want in a Portfolio

Beginning from First Principles, let us ask what characteristics we might desire in an investment portfolio. We posit from Prospect Theory that in general humans are not fully rational actors when making decisions in the face of risk. Individuals are loss averse, resulting in departures in behavior from that which would be expected from the expected utility-maximizing rational actor: we prefer certain outcomes over uncertain ones, even when the price of certainty is a choice that doesn’t maximize utility. Naturally, we prefer portfolios that go up more than they go down, and evidence more certainty of return rather than less.

This is just to say that investors prefer portfolios with higher Sharpe ratios; however, we are more likely to prefer risk when confronting a loss, and more likely to prefer certainty when faced with a gain. This would seem to translate into a portfolio with bond-like upside, and equity-like downside. When the status quo is a moderate gain, losing that gain is more painful than additional gain would be pleasurable. Similarly, when the status quo is a moderate loss, regaining what was lost is more pleasurable than further loss is painful. Thus, Cumulative Prospect Theory leads us to understand that it is gain and loss with respect to a reference point, the status quo ante, that determines our attitude toward additional gain and loss—and especially large, sudden gain or loss. Losses loom larger than gains.

Let us assume for a moment that this combination is desirable—though perhaps somewhat ill-advised—and that we can replicate this combination of payoffs: convex on the downside of the status quo, and concave on the upside. The Balanced Portfolio would seemingly provide this very profile: its corporate bonds behave as equity call options, allowing the investor to participate in corporate profitability (a derivative of economic growth) up to that point at which the average corporate bond yield equals the average corporate earnings yield. In effect, the investor has foregone additional equity upside as if she had sold calls on corporate operating profitability.

For our analogy to hold, we must determine whether a premium was received in exchange for writing the option and, if not realized in a receipt of cash, what happens to that premium. Theoretically, the Balanced Portfolio is only exposed to downside risk to the extent of its equity exposure: if the value of its equity holdings were to go to zero, the portfolio would presumably be backstopped by the recovery value of the corporate assets that perfect its corporate bonds’ security interest. This downside protection is similar in nature to having purchased a put. Thus, the Balanced Portfolio investor has used her premium from selling her call to purchase a put, and so in toto has replicated a protective collar option strategy.

Perhaps Not Irrational, but Satisficing Nonetheless

When viewed from this perspective, the Balanced Portfolio makes a kind of sense; in exchange for a lower bound on downside risk, the investor surrenders some upside risk. The relative weights of equities to bonds in the portfolio allow the investor to find that combination of strike prices that creates a corridor with tolerance sufficient for her concave-convex risk preference to transit. The first chart below shows the ‘S’-shaped function of a typical person’s risk preference with regard to the status quo (“Reference point”). This demonstrates the convex risk-seeking preference the investor has when wealth falls below the status quo: the utility of wealth regained is convex up to the status quo. Once wealth increases above the status quo, the function becomes concave, and the utility of newfound wealth diminishes as it exceeds the status quo.

If we assume that the Balanced Portfolio follows from a desirable set of preferences, and given that the Balanced Portfolio is, in a sense, a “synthetic” protective collar that attempts to satisfy these preferences, the question then becomes whether it can be improved, either using derivatives for hedging or by including other instruments for diversification.

A Better Mousetrap

In the case of both the Balanced Portfolio, the excessive concentration of the source of risk and reliance upon an imperfect hedging strategy resulted in an unexpected degree of loss. Returning to the question of what we would wish to see in a portfolio, it is not necessarily robustness or resilience to business cycle downturn, but rather the property of anti-fragility, or positive convexity in response to portfolio stress, that we would wish to observe.

We are, therefore, not so much concerned with building portfolios that hedge downside risk, but rather ones that gain from regime instability. As such, the portfolio that best fits the concave-convex utility function is not merely one with long S&P 500 exposure that dynamically sells calls and buys puts, but one that outperforms during periods of market and financial stress.

As aforementioned, nearly all assets that investors build their portfolios around derive their return from economic growth: when growth is positive, stocks, credit-risky bonds, commodities, real estate, and currencies tend to perform well; when economic growth falls, corporate earnings contract, default rates increase, expected recoveries decline, miners and farmers idle capacity, and rents fall. Exposure to these asset classes is really exposure to the economic growth factor with varying degrees of time lead or lag. The ability to sell short these assets provides a means by which an investor can harvest return during periods of economic downturn; but the only source of return for the long investor during these periods is a well-timed investment in non-credit risky bonds. Even then return is contingent upon the existence of positive real rates—which is certainly not assured as when the policy rate is up against the Zero Lower Bound as had been the case from the end of the Global Financial Crisis until February of 2022 when the Federal Reserve embarked upon its recent and vertiginous interest rate hike.

Volatility and Optionality in Common Alternatives Strategies

At root, Volatility Strategies allow us to gain exposure to the Regime Stability factor. In company with the Economic and Inflation factors, the Regime Stability factor influences outcomes in financial markets. Whereas the Economic Factor gives us exposure to the increase or decrease in Productivity, and the Inflation Factor gives us exposure to the increase or decrease in Money, the Regime Stability Factor gives us exposure to the increase or decrease in Volatility.

Thus, Regime Stability is directly proportional to both a system’s actors’ confidence in the integrity of the system, as well as their certainty regarding the rules that govern the system. Regime stability is typically higher in developed markets, and lower in emerging ones; it is higher when principal-agent problems are low, and it is lower when fears of adverse selection are high.

The primary justification for investing in Alternatives has been rooted in the observation that during periods of crisis they tend to outperform equities, and thus improve portfolio efficiency. The variety of, lack of transparency into, and frequently opportunistic nature of Alternatives strategies makes analysis of returns and contributions to risk and return within a portfolio difficult. However, we can generally say that Alternatives are supposed to exhibit the payoff profile we identified earlier as being desirable: partial upside capture, with limited downside capture. Since the Balanced Portfolio already provides exposure to the Equity Risk Premium, it hardly needs more of it, much less on a levered basis; it is the downside protection Alternatives afford that is attractive, the long volatility feature that improves portfolio efficiency.

Redefining the Balanced Portfolio

First, we analyze the performance of the 60/40 portfolio over the last 47 years and use this as our benchmark. We then divide the period into sub-periods to isolate performance during different regimes. We use the S&P 500 Total Return Index to represent the equity allocation and the Bloomberg (formerly Lehman) US Aggregate Bond Index to represent the bond allocation. We use a constant 60% equities, 40% fixed income allocation, and for simplicity assume no transaction costs. Returns are calculated monthly to represent a typical rebalancing cadence.

We use the Sharpe ratio to determine the efficiency of the Balanced Portfolio and the incremental improvement we make through the addition of new investments, and endeavor to improve the Sharpe ratio of the Balanced Portfolio by reducing its volatility or improving its historical return. To improve the Sharpe ratio, we add an investment in Volatility, represented by the VIX, that is negatively correlated with the Balanced Portfolio. To begin, the Balanced Portfolio exhibits a Sharpe ratio of .12, compared with the Sharpe ratio of the S&P 500 of .09, and the Bloomberg US Agg of .13. Were we to begin with a simple mean-variance optimization of the Balanced Portfolio as well as its constituents and potential diversifiers, we would obtain a portfolio of only two assets: the S&P 500 with an 85% allocation, and the VIX, with a 15% allocation. The resulting portfolio features an expected annual return of 4.9%, an annual volatility of 3.1%, and a Sharpe ratio of .95, a dramatic improvement in efficiency.

Comparison of Balanced Portfolio, Hedged Portfolio

Excluding all other potentially diversifying instruments—including the Bloomberg US Agg—a portfolio of 85% S&P 500 and 15% VIX dominates all other portfolios from January 2005 to April 2023. For convenience, we will refer to this as the “Hedged Portfolio”. Curiously, performance during the GFC is only slightly improved. As can be seen in the drawdown charts below, the drawdown in 2008 was only marginally mitigated by the inclusion of Long Volatility exposure, although performance in 2020 is markedly improved.

Over the period 2005 to 2023, the S&P 500 had a Sharpe ratio of 1.23, the Bloomberg US Agg of 1.48, the VIX of 1.19, the Balanced Portfolio of 1.42, and the Hedged Portfolio of 3.1.

Clearly the inclusion of Long Volatility in our portfolio dramatically improves efficiency. Unfortunately, it can be a dramatically expensive improvement: maintaining the VIX position requires constant rebalancing and transacting in the markets, often at times when VIX trades well above its long-term average price due to its well-documented clustering effects. However, these costs can be mitigated by the use of dynamic allocations that change depending upon the price of Volatility.

Conclusion

We know that asset values are sensitive to Volatility, and that when Volatility is high, asset values fall, just as they rise when Volatility is low. As we have demonstrated with the improvement in our Sharpe ratios through the inclusion of Long Volatility assets, we suggest that the Balanced Portfolio’s response to increases in volatility can be enhanced with respect to the convexity of its response by the inclusion of dynamic exposures, long and short, to the Regime Stability factor. However, we also find that, although we have improved the efficiency of the portfolio through the inclusion of these assets, it is not a silver bullet, and must be paired with the Risk-Free Asset to provide real balance. Bonds will not be so easily supplanted in the Balanced Portfolio. But using Long Volatility, we can build a far more 'balanced' portfolio.

*The foregoing is a summary of the paper, "Small Vol: Constructing Anti-Fragile Portfolios". Please contact us directly for a full version of the paper, or to discuss its insights.