The Hardest Thing to Do

Is to Have Discipline Around Diversification

Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days. Give a portion to seven, and also to eight; for thou knowest not what evil shall be upon the earth.

Ecclesiastes 11.1-2

It has been called the only free lunch in finance.1 Effective portfolio diversification is a truly remarkable thing, as it can lower the total risk of a portfolio of investments—as measured by the volatility of portfolio return—without a commensurate diminution of total return. No other academic theory has been more responsible for the landscape of the modern markets, as index investing is its direct consequence.

Yet, diversification can result in underperformance by risk or return measures over insufficiently long measurement periods. From 2023 to 2024, there was no better trade as measured by its Sharpe ratio than Bitcoin: its gains were stratospheric and its volatility was far reduced compared to its prior penchant for large price change. During the same period, the S&P500—or, more accurately, the Magnificent Seven group of stocks—exhibited a similarly asymptotic ascent in price. This is characteristic of the “number go up” profile that irrational exuberance2 imparts to speculative bubbles:

Irrational exuberance is the psychological basis of a speculative bubble. I define a speculative bubble as a situation in which news of price increases spurs investor enthusiasm, which spreads by psychological contagion from person to person, in the process amplifying stories that might justify the price increases, and bringing in a larger and larger class of investors who, despite doubts about the real value of an investment, are drawn to it partly by envy of others' successes and partly through a gamblers' excitement.

But while these manias rage, their subject is often a good investment—at least as measured by a ratio of excess return to the volatility of return. Returns only go one way, and they do so steadily. As their price increases, so does their capitalization, which in turn pulls the entire index upward. We see this in the relative price/earnings ratios of the Magnificent Seven and the S&P493.

So, the Magnificent Seven group of stocks have been historically great investments. Momentum-following algorithms have picked up on the trend and have contributed to their upward trajectory, too, to the point where the Magnificent Seven represents an uncomfortably large percentage of the index, with the result that the index is no longer effectively diversified.

As we mentioned earlier, it is effective portfolio diversification that matters for the purpose of improving the efficiency of investment portfolios. An overly large concentration of technology and technology-adjacent stocks in an index alters the character of that index, reducing its diversification benefit. It is the index’ overexposure to the growth and quality factors that is the largest single risk to the investor in US large cap stocks.

This is not to say that high volatility investments don’t belong in a diversified portfolio. To the contrary, high volatility investments—even those with negative expected return—are critical to portfolio diversification, provided that the volatility comes from investments with low or negative correlation to the portfolio. And this is the insight-behind-the-insight in Markowitz’ paper: it is the asset prices’ co-movements that are most important in the context of risk reduction.

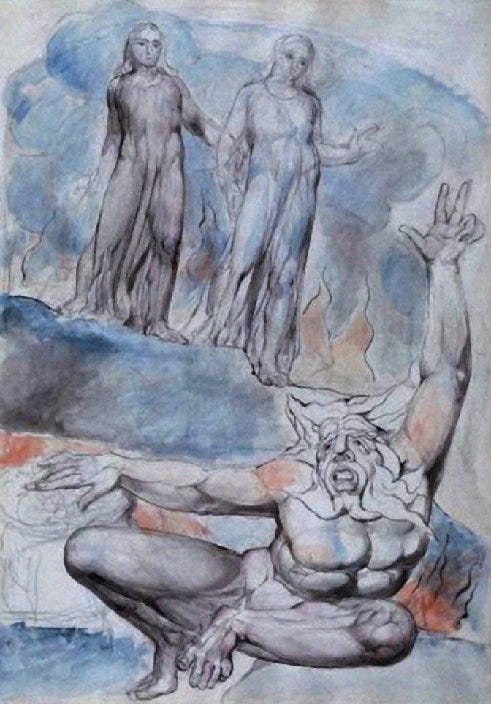

It is difficult to hear friends and acquaintances crow about the extraordinary sums they’ve made in digital assets and the Exuberant Septet. Envy is a deeply rooted emotion, as it likely conferred some evolutionary advantage in the distant past. One can imagine that it inspired many a hungry hunter-gatherer to doggedly stalk their hale clanmate to a hidden, cerebrum-expanding honey hole. In investing, however, returns-chasing behavior too often ends in tears. An intention to buy low to later sell high is frequently reified in buying high only to later sell low. To maintain the slope of price increases these assets have traced over the past two years requires them to double yet again—a truly magnificent feat.

That we are at or past the peak price action in digital assets and the Exuberant Septet is suggested by their recent underperformance of the Global Market Portfolio (GMP). BTC has lost 23% from its all-time high. The Bloomberg Magnificent 7 Total Return Index has declined 10.7% from its all-time high on December 17, as of Tuesday’s close. The S&P500 is 3.3% off of its all-time high. That these assets are trading sideways-to-down with highly volatile price action suggests that they are struggling to find marginal buyers—and so are finding marginal sellers instead.

Meanwhile, goodstead favorites the STOXX Europe 600 index has gained more than 11.4%, and the EURO STOXX 50 index has gained a similar 14% over the same period of time. It did not require a keen analytical wit to obtain these returns: it merely required the discipline to remain invested.

That we believe the US equity market is in the midst of an AI-fueled bubble is no surprise to our regular readers. We don’t know—and no one can know—how this radical new technology will ultimately affect the way we live and work. We can offer the anecdote that it has made our plucky band of underdogs vastly more productive. But in fact, it is the latest, least-expensively developed LLM that we find ourselves using the most frequently and from which we obtain the most dependable results. This does not bode well for the corporate behemoths who have abandoned capital discipline in their existential race for survival.

Fortunately, we don’t need to know. While we take factor tilts on the GMP based on a variety of fundamental and quantitative relationships, we maintain a broadly diversified portfolio. We will participate, then, in the Exuberant Septet’s potential successes—as well as its failures—to the extent that we think it prudent. But we will participate far more in the broader equity market, and the economic growth factor of which it is derivative, even if it means leaving some winnings on the table from time to time as tribute to Plutus, whose desire for them is unslakable.

Attributed, perhaps apocryphally, to Harry Markowitz, [Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred] Nobel Laureate and one of the founders of Modern Portfolio Theory. The original insight comes from his 1952 The Journal of Finance paper, “Portfolio Selection”.

The title of [Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred] Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller’s prescient book on the late 90’s excessive enthusiasm for internet and telecommunications stocks. It is unsurprisingly a salient read in the current environment.